Overview

Teaching: 30 min Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I make sure my programs are correct?

Objectives

Explain what an assertion is.

Add assertions to programs that correctly check the program’s state.

Correctly add precondition and postcondition assertions to functions.

Explain what test-driven development is, and use it when creating new functions.

Explain why variables should be initialized using actual data values rather than arbitrary constants.

Debug code containing an error systematically.

Our previous lessons have introduced the basic tools of programming: variables and lists, file I/O, loops, conditionals, and functions. What they haven’t done is show us how to tell whether a program is getting the right answer, and how to tell if it’s still getting the right answer as we make changes to it.

To achieve that, we need to:

- write programs that check their own operation,

- write and run tests for widely-used functions, and

- make sure we know what “correct” actually means.

The good news is, doing these things will speed up our programming, not slow it down.

The first step toward getting the right answers from our programs is to assume that mistakes will happen and to guard against them. This is called defensive programming, and the most common way to do it is to add assertions to our code so that it checks itself as it runs. An assertion is simply a statement that something must be true at a certain point in a program. When MATLAB sees one, it checks the assertion’s condition. If it’s true, MATLAB does nothing, but if it’s false, MATLAB halts the program immediately and prints an error message. For example, this piece of code halts as soon as the loop encounters a value that isn’t positive:

numbers = [1.5, 2.3, 0.7, -0.001, 4.4];

total = 0;

for n = numbers

assert(n >= 0);

total = total + n;

end

error: assert (n >= 0) failed

Programs like the Firefox browser are full of assertions: 10-20% of the code they contain are there to check that the other 80-90% are working correctly. Broadly speaking, assertions fall into three categories:

- A precondition is something that must be true at the start of a function in order for it to work correctly.

- A postcondition is something that the function guarantees is true when it finishes.

- An invariant is something that is always true at a particular point inside a piece of code.

For example, suppose we are representing rectangles using an array of four coordinates

(x0, y0, x1, y1), such that (x0,y0) are the bottom left coordinates,

and (x1,y1) are the top right coordinates. In order to do some calculations,

we need to normalize the rectangle so that it is at the origin, measures 1.0

units on its longest axis, and is oriented so the longest axis is the y axis.

Here is a function that does that, but checks that its input is correctly

formatted and that its result makes sense:

function normalized = normalize_rectangle(rect)

% Normalizes a rectangle so that it is at the origin

% measures 1.0 units on its longest axis

% and is oriented with the longest axis in the y direction:

assert(length(rect) == 4, 'Rectangle must contain 4 coordinates');

x0 = rect(1);

y0 = rect(2);

x1 = rect(3);

y1 = rect(4);

assert(x0 < x1, 'Invalid X coordinates');

assert(y0 < y1, 'Invalid Y coordinates');

dx = x1 - x0;

dy = y1 - y0;

if dx > dy

scaled = dx/dy;

upper_x = scaled;

upper_y = 1.0;

else

scaled = dx/dy;

upper_x = scaled;

upper_y = 1.0;

end

assert ((0 < upper_x) && (upper_x <= 1.0), 'Calculated upper X coordinate invalid');

assert ((0 < upper_y) && (upper_y <= 1.0), 'Calculated upper Y coordinate invalid');

normalized = [0, 0, upper_x, upper_y];

end

The three preconditions catch invalid inputs:

normalize_rectangle([0, 0, 1])

Error using normalize_rectangle (line 6)

Rectangle must contain 4 coordinates

normalize_rectangle([1,0,0,0,0])

Error: Rectangle must contain 4 coordinates

normalize_rectangle([1, 0, 0, 2]);

error: Invalid X coordinates

The post-conditions help us catch bugs by telling us when our calculations cannot have been correct. For example, if we normalize a rectangle that is taller than it is wide, everything seems OK:

normalize_rectangle([0, 0, 1.0, 5.0]);

0.00000 0.00000 0.20000 1.00000

but if we normalize one that’s wider than it is tall, the assertion is triggered:

normalize_rectangle([0.0, 0.0, 5.0, 1.0])

error: Calculated upper X coordinate invalid

Re-reading our function, we realize that line 19 should

should divide dy by dx. If we had left out the assertion

at the end of the function, we would have created and

returned something that had the right shape as

a valid answer, but wasn’t. Detecting and debugging that

would almost certainly have taken more time in

the long run than writing the assertion.

But assertions aren’t just about catching errors: they also help people understand programs. Each assertion gives the person reading the program a chance to check (consciously or otherwise) that their understanding matches what the code is doing.

Most good programmers follow two rules when adding assertions to their code. The first is, fail early, fail often. The greater the distance between when and where an error occurs and when it’s noticed, the harder the error will be to debug, so good code catches mistakes as early as possible.

The second rule is, turn bugs into assertions or tests. If you made a mistake in a piece of code, the odds are good that you have made other mistakes nearby, or will make the same mistake (or a related one) the next time you change it. Writing assertions to check that you haven’t regressed (i.e., haven’t re-introduced an old problem) can save a lot of time in the long run, and helps to warn people who are reading the code (including your future self) that this bit is tricky.

Finding Conditions

Suppose you are writing a function called

averagethat calculates the average of the numbers in a list. What pre-conditions and post-conditions would you write for it? Compare your answer to your neighbor’s: can you think of an input array that will past your tests but not hers or vice versa?

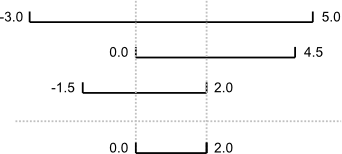

An assertion checks that something is true at a particular point in the program. The next step is to check the overall behavior of a piece of code, i.e., to make sure that it produces the right output when it’s given a particular input. For example, suppose we need to find where two or more time series overlap. The range of each time series is represented as a pair of numbers, which are the time the interval started and ended. The output is the largest range that they all include:

Most novice programmers would solve this problem like this:

- Write a function

range_overlap. - Call it interactively on two or three different inputs.

- If it produces the wrong answer, fix the function and re-run that test.

This clearly works–after all, thousands of scientists are doing it right now–but there’s a better way:

- Write a short function for each test.

- Write a

range_overlapfunction that should pass those tests. - If

range_overlapproduces any wrong answers, fix it and re-run the test functions.

Writing the tests before writing the function they exercise is called test-driven development (TDD). Its advocates believe it produces better code faster because:

-

If people write tests after writing the thing to be tested, they are subject to confirmation bias, i.e., they subconsciously write tests to show that their code is correct, rather than to find errors.

-

Writing tests helps programmers figure out what the function is actually supposed to do.

Below are three test functions for range_overlap, but first we need a brief aside to explain some MATLAB behaviour.

-

Argument format required for

assertassertrequires a scalar logical input argument (i.e.true(1) orfalse(0)). -

Testing for equality between matrices

The syntax

matA == matBreturns a matrix of logical values. If we just want atrueorfalseanswer for the whole matrix (e.g. to use withassert), we need to useisequalinstead.

Looking For Help

For a more detailed explanation, search the MATLAB help files (or type

doc eq; doc assertat the command prompt).

% script test_range_overlap.m

% assert(isnan(range_overlap([0.0, 1.0], [5.0, 6.0])));

% assert(isnan(range_overlap([0.0, 1.0], [1.0, 2.0])));

assert(isequal(range_overlap([0, 1.0]),[0, 1.0]));

assert(isequal(range_overlap([2.0, 3.0], [2.0, 4.0]),[2.0, 3.0]));

assert(isequal(range_overlap([0.0, 1.0], [0.0, 2.0], [-1.0, 1.0]),[0.0, 1.0]))

test_range_overlap

Undefined function or variable 'range_overlap'.

Error in test_range_overlap (line 6)

assert(isequal(range_overlap([0, 1.0]),[0, 1.0]));

The error is actually reassuring:

we haven’t written range_overlap yet,

so if the tests passed,

it would be a sign that someone else had

and that we were accidentally using their function.

And as a bonus of writing these tests, we’ve implicitly defined what our input and output look like: we expect a list of pairs as input, and produce a single pair as output.

Let’s write range_overlap:

function output_range = range_overlap(varargin)

% Return common overlap among a set of [low, high] ranges.

lowest = -inf;

highest = +inf;

for i = 1:nargin

range = varargin{i};

low = range(1);

high = range(2);

lowest = max(lowest, low);

highest = min(highest, high);

end

output_range = [lowest, highest];

end

And now when we run the tests:

test_range_overlap

we shouldn’t see an error.

Something important is missing, though. We don’t have any tests for the case where the ranges don’t overlap at all, or for the case where the ranges overlap at a point. We’ll leave this as a final assignment.

Fixing Code Through Testing

Fix

range_overlap. Uncomment the two commented lines intest_range_overlap. You’ll see that our objective is to return a special value:NaN(Not a Number), for the following cases:

- The ranges don’t overlap.

- The ranges overlap at their endpoints.

As you make change to the code, run

test_range_overlapregularly to make sure you aren’t breaking anything. Once you’re done, runningtest_range_overlapshouldn’t raise any errors.Hint: read about the

isnanfunction in the help files to make sure you understand what these first two lines are doing.

Once testing has uncovered problems, the next step is to fix them. Many novices do this by making more-or-less random changes to their code until it seems to produce the right answer, but that’s very inefficient (and the result is usually only correct for the one case they’re testing). The more experienced a programmer is, the more systematically they debug, and most follow some variation on the rules explained below.

The first step in debugging something is to know what it’s supposed to do. “My program doesn’t work” isn’t good enough: in order to diagnose and fix problems, we need to be able to tell correct output from incorrect. If we can write a test case for the failing case—i.e., if we can assert that with these inputs, the function should produce that result—then we’re ready to start debugging. If we can’t, then we need to figure out how we’re going to know when we’ve fixed things.

But writing test cases for scientific software is frequently harder than writing test cases for commercial applications, because if we knew what the output of the scientific code was supposed to be, we wouldn’t be running the software: we’d be writing up our results and moving on to the next program. In practice, scientists tend to do the following:

-

Test with simplified data. Before doing statistics on a real data set, we should try calculating statistics for a single record, for two identical records, for two records whose values are one step apart, or for some other case where we can calculate the right answer by hand.

-

Test a simplified case. If our program is supposed to simulate magnetic eddies in rapidly-rotating blobs of supercooled helium, our first test should be a blob of helium that isn’t rotating, and isn’t being subjected to any external electromagnetic fields. Similarly, if we’re looking at the effects of climate change on speciation, our first test should hold temperature, precipitation, and other factors constant.

-

Compare to an oracle. A test oracle is something—experimental data, an older program whose results are trusted, or even a human expert—against which we can compare the results of our new program. If we have a test oracle, we should store its output for particular cases so that we can compare it with our new results as often as we like without re-running that program.

-

Check conservation laws. Mass, energy, and other quantities are conserved in physical systems, so they should be in programs as well. Similarly, if we are analyzing patient data, the number of records should either stay the same or decrease as we move from one analysis to the next (since we might throw away outliers or records with missing values). If “new” patients start appearing out of nowhere as we move through our pipeline, it’s probably a sign that something is wrong.

-

Visualize. Data analysts frequently use simple visualizations to check both the science they’re doing and the correctness of their code (just as we did in the opening lesson of this tutorial). This should only be used for debugging as a last resort, though, since it’s very hard to compare two visualizations automatically.

We can only debug something when it fails, so the second step is always to find a test case that makes it fail every time. The “every time” part is important because few things are more frustrating than debugging an intermittent problem: if we have to call a function a dozen times to get a single failure, the odds are good that we’ll scroll past the failure when it actually occurs.

As part of this, it’s always important to check that our code is “plugged in”, i.e., that we’re actually exercising the problem that we think we are. Every programmer has spent hours chasing a bug, only to realize that they were actually calling their code on the wrong data set or with the wrong configuration parameters, or are using the wrong version of the software entirely. Mistakes like these are particularly likely to happen when we’re tired, frustrated, and up against a deadline, which is one of the reasons late-night (or overnight) coding sessions are almost never worthwhile.

If it takes 20 minutes for the bug to surface, we can only do three experiments an hour. That doesn’t mean we’ll get less data in more time: we’re also more likely to be distracted by other things as we wait for our program to fail, which means the time we are spending on the problem is less focused. It’s therefore critical to make it fail fast.

As well as making the program fail fast in time, we want to make it fail fast in space, i.e., we want to localize the failure to the smallest possible region of code:

-

The smaller the gap between cause and effect, the easier the connection is to find. Many programmers therefore use a divide and conquer strategy to find bugs, i.e., if the output of a function is wrong, they check whether things are OK in the middle, then concentrate on either the first or second half, and so on.

-

N things can interact in N2 different ways, so every line of code that isn’t run as part of a test means more than one thing we don’t need to worry about.

Replacing random chunks of code is unlikely to do much good. (After all, if you got it wrong the first time, you’ll probably get it wrong the second and third as well.) Good programmers therefore change one thing at a time, for a reason. They are either trying to gather more information (“is the bug still there if we change the order of the loops?”) or test a fix (“can we make the bug go away by sorting our data before processing it?”).

Every time we make a change, however small, we should re-run our tests immediately, because the more things we change at once, the harder it is to know what’s responsible for what (those N2 interactions again). And we should re-run all of our tests: more than half of fixes made to code introduce (or re-introduce) bugs, so re-running all of our tests tells us whether we have regressed.

Good scientists keep track of what they’ve done so that they can reproduce their work, and so that they don’t waste time repeating the same experiments or running ones whose results won’t be interesting. Similarly, debugging works best when we keep track of what we’ve done and how well it worked. If we find ourselves asking, “Did left followed by right with an odd number of lines cause the crash? Or was it right followed by left? Or was I using an even number of lines?” then it’s time to step away from the computer, take a deep breath, and start working more systematically.

Records are particularly useful when the time comes to ask for help. People are more likely to listen to us when we can explain clearly what we did, and we’re better able to give them the information they need to be useful.

Version control is often used to reset software to a known state during debugging,

and to explore recent changes to code that might be responsible for bugs.

In particular,

most version control systems have a blame command

that will show who last changed particular lines of code…

And speaking of help: if we can’t find a bug in 10 minutes, we should be humble and ask for help. Just explaining the problem aloud is often useful, since hearing what we’re thinking helps us spot inconsistencies and hidden assumptions.

Asking for help also helps alleviate confirmation bias. If we have just spent an hour writing a complicated program, we want it to work, so we’re likely to keep telling ourselves why it should, rather than searching for the reason it doesn’t. People who aren’t emotionally invested in the code can be more objective, which is why they’re often able to spot the simple mistakes we have overlooked.

Part of being humble is learning from our mistakes. Programmers tend to get the same things wrong over and over: either they don’t understand the language and libraries they’re working with, or their model of how things work is wrong. In either case, taking note of why the error occurred and checking for it next time quickly turns into not making the mistake at all.

And that is what makes us most productive in the long run. As the saying goes, A week of hard work can sometimes save you an hour of thought. If we train ourselves to avoid making some kinds of mistakes, to break our code into modular, testable chunks, and to turn every assumption (or mistake) into an assertion, it will actually take us less time to produce working programs, not more.

Key Points

Use assertions to catch errors, and to document what behavior is expected.

Initialize variables with actual values rather than arbitrary constants.

Write tests before code.