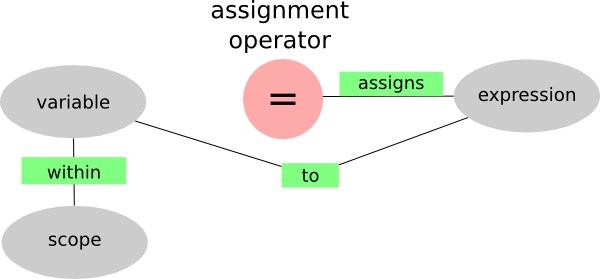

Think of =, which is the assignment operator, as filling out of a lanyard or name tag or label that someone is going to wear around their head/neck. The variable name is to the left of the =, and the person it labels is to the right. From then on, you can refer to whoever gets the nametag by the label on it. Suppose there’s already someone named Finn in our code. We make make Finn a new nametag:

coolest_hero = Finn

Turns out that anyone can wear more than one label and labels exist within a context (some scope). If the idea of having multiple names seems odd, consider Finn at a conference: he might be referred to by his name as just “Finn”, now also as “coolest_hero” or as “Attendee #114″ for the purposes of a prize drawing, or also as “moderator of the first panel”.

attendee_114 = Finn moderator_panel_1 = Finn

These last two make sense as labels for the duration of the conference, and indeed, during *his* panel, Finn might simple be referred to simply as “moderator”.

while panel_1_in_session:

moderator = Finn

...

But someone else will have that label during the other panels.

while panel_2_in_session:

moderator = Jake

...

One caveat about the limitations of this analogy is that within a context, all labels are unique, so that when Finn’s hero Billy arrives at the conference, we transfer the “coolest hero” tag to Billy, and anyone referring to “coolest hero” from then on would be referring to Billy.

coolest_hero = Billy

We can assign a new label to someone referred by another. For example, let’s make another label for referring to Billy:

last_arrival = coolest_hero

We can also do the above two assignments in one line, because a given expression can get assigned to multiple variable at the same time.

last_arrival = coolest_hero = Billy

In general, any expression can go on the right hand side of an assignment. Suppose that Finn and Jake know how to to combine into a dynamic duo, when you add them together:

dynamic_duo = Finn + Jake

Or getting back to something simpler, we can label things, as well as people — let’s label a number.

lucky_number = 3 + 4

The right hand side gets evaluated first, so first the expression 3+” gets evaluated to 7, and then 7 gets assigned to “luck_number”.

Because the right hand side gets evaluated first, you sometimes see a variable name on both sides.

lucky_number = 6 * lucky_number

So on the right hand side, “lucky_number” was a label for 7, but after the expression 6*7 evaluated to 42, 42 was assigned back to the variable “lucky_number”. Recall that we can only have one “lucky_number” within a scope, just like we could only have one “coolest_hero”.