Prepared by Justin Kitzes

[JK: Since lists are a somewhat complex subject, I wrote short vignette/examples below rather than code snippets + paragraphs. Hopefully still in the spirit of the assignment.]

A Mainstream Example

You are selling pumpkins at the farmer’s market and tracking your daily transactions. Usually transactions are sales (positive number), but there may occasionally be a refund of an earlier purchase (negative number).

You get started by entering the first five transactions of the day. You use a list to hold five numbers, one for each transaction. Four of these were sales, and one was a refund.

trans = [5, 3, 12, -2, 20]

There’s a lull in the action, and you take a minute to check in on how you’ve been doing so far.

print sum(trans) # See total net income so far print len(trans) # See how many transactions you've done today print [t for t in trans if t < 0] # See list of all refunds

A new customer arrives and buys a pie pumpkin, and you add a $10 sale to your list of transactions.

trans.append(10) # Add a new $10 sale

While counting change for this last sale, you realize that the first customer of the day only gave you $4 instead of the $5 that he owed you. You check in on the value that you entered for the first transaction, see that you put in $5, and correct it to $4.

print trans[0] # See value of first transaction trans[0] = 4 # Correct value of first sale to $4, not $5

Since you got distracted, you make sure that you entered the last pie pumpkin transaction correctly as $10, which you did.

print trans[-1] # See value of last transaction

Before heading home, you’re curious how much you grossed today, ignoring any refunds. You calculate this with a for loop.

gross = 0

for t in trans: # Calculate gross income

if t > 0:

gross = gross + t

print gross

Contrasting Example

The next week, you learned about another way of storing collections of items in Python, called a tuple. You’re not really sure what the difference is, but you decide to try using a tuple instead of a list this week.

As before, you enter your first five transactions of the day, but you use parenthesis () instead of square brackets [] to make your collection a tuple instead of a list.

trans = (1, 8, 50, 2, 10)

Everything is going great until you try to add a new transaction for $8.

trans.append(8) > AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

That’s odd, apparently you can’t use append to add new transactions. You try a few other things, and also realize that you can’t change previous transactions.

print trans[0] # Works fine > 1 trans[0] = 2 > TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

This is strange, because tuples and lists seemed to work exactly the same way, except that it looks like tuples don’t let you add or change any of their elements.

Since it’s a slow day, you look up the difference between tuples and lists in the online Python documentation and find that tuples are not mutable — they cannot be changed after they are created — while lists are mutable. You realize quickly that you need to go back to using lists. You find that you can convert your tuple to a list pretty easily, however, and continue your day of pumpkin selling.

trans = list(trans)

You’re pretty annoyed at that guy Justin who taught you about tuples in the first place, so you write the following program and email it to him.

new_list = ["Justin", "is", "a"]

new_list.append("great guy.") # See what lists let me do!

new_list[3] = "jerk."

for word in new_list:

print word

You later discover, incidentally, that some (though not all) Pythonistas believe there is an additional philosophical difference between lists and tuples, which is that tuples (perhaps because they are immutable) should be used to contain groups of items that are conceptually distinct and in which the location of the item in the group defines which concept it represents. For example,

favorite_movie = ('Avatar', 'James Cameroon', 2009)

worst_movie = ('Edward Scissorhands', 'Tim Burton', 1990)

where the items are the title, director, and year — different concepts, and the location of an item in the tuple tells you which concept it refers to. x and y coordinates being stored as (x, y) is another common example.

In contrast, lists are suggested for groups in which items may come sequentially, but in which all items refer to the same concept.

movies_watched_this_month = ['Avatar', 'Cars', 300, 'Jaws']

Here, even though the data types are not all strings (300 is an int here), these are all movie titles and hence represent the same concept. The order may still represent the order in which I saw the movies, however. If order is really irrelevant, a set may be more appropriate (philosphically) than a list.

See

http://news.e-scribe.com/397

http://www.hacksparrow.com/python-difference-between-list-and-tuple.html.

Deeper concepts

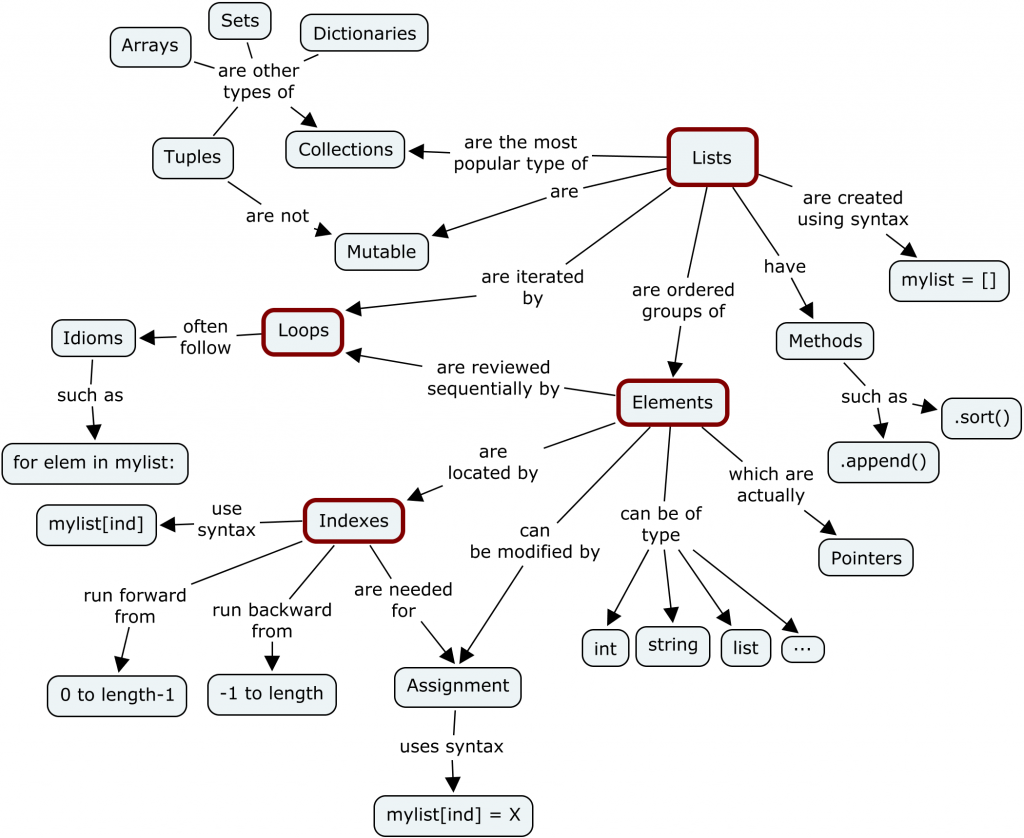

The main example hits on several major features of lists, including (1) declaration syntax, (2) the operations sum and length, (3) indexing, including negative indexing, (4) assignment, and (5) iterating. The contrasting example with tuples additionally introduces (1) the tuple collection and its declaration syntax, (2) differences in mutability between tuples and lists, (3) type casting, and (4) a list with string instead of integer elements.

The examples together highlight the two more general concepts of collections (by providing two examples with mostly similar behavior) and mutability (by contrasting lists and tuples). Readers will need some prior knowledge of basic Python syntax, print, data types, and for loops / control statements.

Other

It took me around 4-5 hours (including the reading) to complete this week’s assignment, although I didn’t make too much of an effort to work quickly. I downloaded CmapTools to use to make my concept map — great free software, very easy to use.