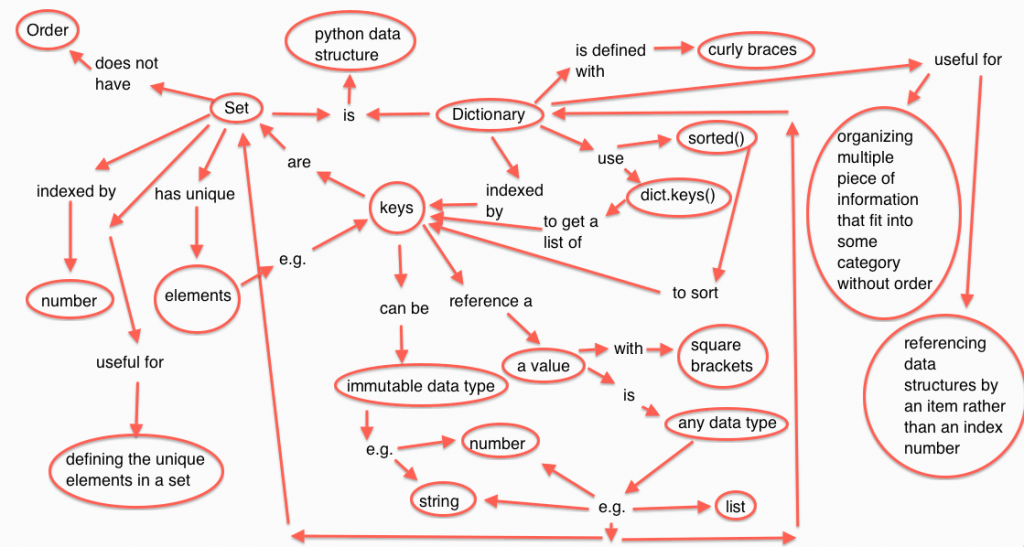

Concept Map:

Example:

**You are teaching a class and wish to store homework and test scores in an easily accessible way. You make a dictionary with student names as keys. For each key (student’s name) you create another dictionary with keys: ‘test’ and ‘homework’. Both test and homework reference lists with the student’s test scores and homework scores. The dictionary looks like this:

student_scores_dict = {‘Adele’: {‘test’: [70.0, 75.0], ‘homework’: [90.0, 91.5, 90.2, 89.0, 95.0]},

'James': {'test': [60.0, 80.1], 'homework': [80.0, 85.0, 83.0, 89.0, 82.5]},

'Martha': {'test': [90.0, 95.0], 'homework': [90.0, 91.0, 92.0, 95.0, 92.5]}}

Now it is easy to get information on the test and homework scores. For instance, to get the average homework score of each student:

for student_name in student_scores_dict.keys():

print student_name, mean(student_scores_dict[student_name]['homework'])

Contrasting example:

Part 1:

Another way to keep track of groups of items is a tuple. In this case the first element of the tuple would be the students name, the second element the list of test scores, and the third element the list of homework scores. You can store the same information you stored in your dictionary in a list of tuples:

student_scores_tup = [(‘Adele’, [70.0, 75.0],[90.0, 91.5, 90.2, 89.0, 95.0]),

('James', [60.0, 80.1], [80.0, 85.0, 83.0, 89.0, 82.5]),

(Martha', [90.0, 95.0], [90.0, 91.0, 92.0, 95.0, 92.5])]

While this is a valid way to store information, it has three distinct disadvantages: first, you have to remember what order you stored things in (i.e. that test scores are first then homework scores), second, you can’t add to your tuple: you have to create a new tuple, and third, you can’t easily access the record of one student.

For example, the class is given 2 quizzes which were not originally planned and which you want to add to your record keeping scheme.

When you originally gave the quizes, you didn’t have time to integrate them into your data storage structure so you stored the scores in a separate dictionary with the student names as keys and the quiz scores as a list for the value of each key:

student_quiz_scores = {‘Adele’:[80.0, 82.0], ‘James’: [70.0, 75.0], ‘Martha’: [95.0, 96.0]}

You now want to combine all of the scores into a single data structure.

Tuple Case:

Fortunately your tuple list the names in alphabetical order, so you can add the quiz scores by sorting the names and reconstructing the tuple:

student_scores_tup2 = [] #create an empty list for your new list of tuples

for i, student_name in enumerate(sorted(student_quiz_scores.keys())): #sort your list of keys

student_scores_tup2.append((student_scores[i][0], student_scores_tup[i][1], student_scores_tup[i][2], student_quiz_scores[student_name]))

In this case you had to create a new list of new tuples: student_scores_tup2. The ease of this example also relies on the fact that the names in the tuple were in alphabetical order enabling us to loop over them. How would this process change if the names were not in alphabetical order?

Your new tuple looks like this:

student_scores_tup2 = [(‘Adele’, [70.0, 75.0],[90.0, 91.5, 90.2, 89.0, 95.0], [80.0, 82.0]),

('James', [60.0, 80.1], [80.0, 85.0, 83.0, 89.0, 82.5], [70.0, 75.0]),

(Martha', [90.0, 95.0], [90.0, 91.0, 92.0, 95.0, 92.5], [95.0, 96.0])]

It is now easy to see that test scores and quiz scores could easily be mixed up.

Dictionary Case:

To put the new quiz scores into your dictionary, you can add a new key to your inner dictionary (so you now have keys: ‘test’, ‘homework’, and ‘quiz’).

for student_name in student_quiz_scores.keys():

student_scores_dict[student_name]['quiz'] = student_quiz_scores[student_name]

In this case you don’t have to worry about accidentally placing a student’s quiz scores with another student’s name and there is no requirement that the either dictionary have any order. Additionally, you can keep your original data structure by just adding a key. Your new dictionary looks like this:

student_scores_dict = {‘Adele’: {‘test’: [70.0, 75.0], ‘homework’: [90.0, 91.5, 90.2, 89.0, 95.0], ‘quiz’: [80.0, 82.0]},

'James': {'test': [60.0, 80.1], 'homework': [80.0, 85.0, 83.0, 89.0, 82.5], 'quiz': [70.0, 75.0]},

'Martha': {'test': [90.0, 95.0], 'homework': [90.0, 91.0, 92.0, 95.0, 92.5], 'quiz': [95.0, 90.0]}}

Part 2

Finally, you want to find Adele’s lowest homework score.

Tuple Case:

For the tuple data structure you have to know which tuple in the list belongs to Adele, reference it by index number, and remember that the homework score is in the third element of the tuple:

print min(student_scores_tup2[0][2])

Dictionary Case:

For the dictionary data structure, you can reference Adele’s homework data by using her name and ‘homework’ as keys:

print min(student_scores_dict[‘Adele’][‘homework’])

Deep Concepts:

The first part of this example highlights the basic construction of a dictionary using strings for keys. It also includes a nested dictionary and values with list data structures demonstrating the flexibility of the data structure of the values assigned to each key. It then demonstrates accessing elements in a dictionary using the .keys() attribute.

The contrasting case shows the limitations of tuples and the benefits of having keys to reference items. The flexibility of a dictionary is show: the ability to add keys at any time as well as the ability to access any piece of the dictionary independent of the other pieces. The benefits of having the key names to remind you of what items are stored is also shown. This example also shows how you can combine information from 2 dictionaries with the same keys into a single dictionary. It exposes students to the sorted function and will demonstrate that keys are case sensitive.

Time of assignment:

The reading took me about 2.5 hours and creating the concept map and the write up an additional 2 hours = 4.5 hours total

Prerequisite concepts;

Tuples, lists, enumerate, for loop, line continuation