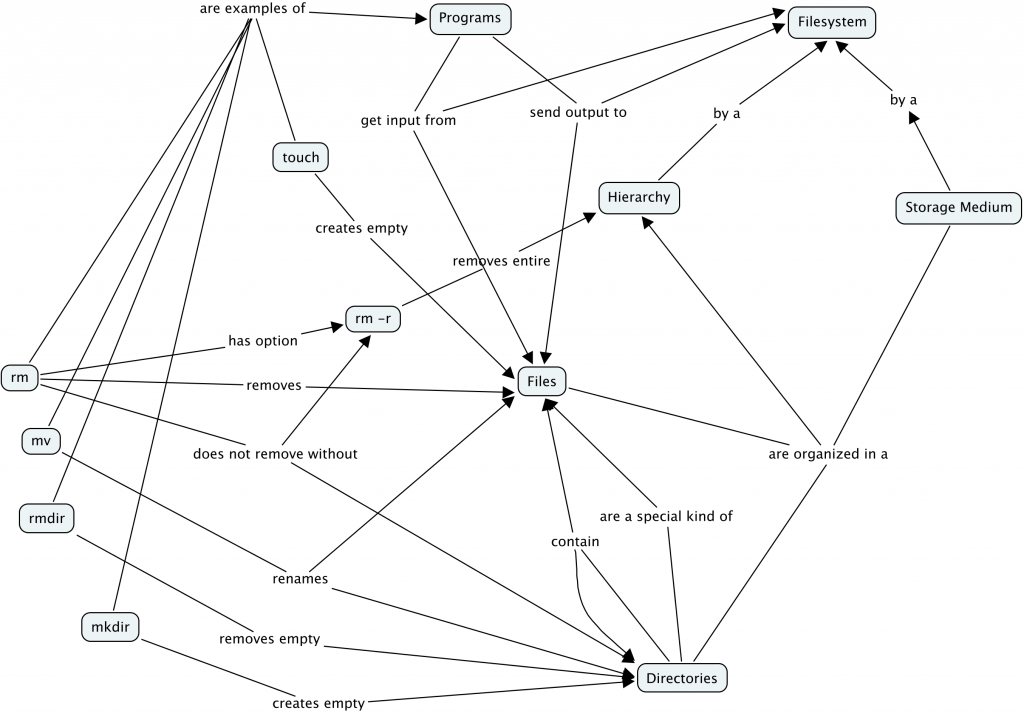

Creating a concept map for creating and destroying files turned out to be surprisingly challenging. My rough draft (sketched unreadably on paper) was vastly more complex, and included deeper concepts about different filesystems and their implementations (inodes, etc.); it included the shell, pipes, and many other concepts that were better left as their own topics, but that were still directly linked to this one. Ideally I would have taken the results of others’ assignments and linked them back to my concept map.

In the end I pared things down quite a bit, and what I was left with I think was lacking in detail about the original assignment, which was creating and destroying files/directories. If I had more time I would probably leave the details of what files and directories are, and how they are organized to a different concept map, and focus more on the actual command-line tools and how they interact. And although concept maps are very useful, the way my thoughts on the topic were organized bumped up against some limitations of the format that I was not sure how to resolve. For example, I could not find a good way to represent the fact that while on on a high level, programs perform I/O with files, on a lower level they actually do I/O with a system library, which in turn talks to the file system (through several other layers of abstraction). Having deep knowledge of a subject makes it difficult to simplify it without feeling like I’m cheating/lying a little bit.

Prerequisite Knowledge**

**

Files and directories are organized in a hierarchical, tree-like “filesystem”. The leaf nodes in this tree can be either files, or directories (which are a special type of file). The internal nodes are all directories. Directories can contain zero or more files and other directories. At the command-line and in software, a file or directory’s full “path” is sequence of the names of all the nodes leading from the root of the filesystem to that file, followed by the name of the file itself. The student should be familiar at this point with this concept, and how paths are textually represented in UNIX systems. The student should also be familiar with navigating the filesystem hierarchy on the command-line, and with listing files. These topics should be covered in other sections.

A Mainstream Example

**Any program that can write to a file can, in most cases, create (and write to) a new empty file. One of the simplest programs that can create a file is called `touch`. It simply creates an empty file on the filesystem. If given a filename, touch creates a file with that name in the current working directory:

$ ls $ touch __init__.py $ ls -l total 0 -rw-r--r-- 1 embray science 0 Sep 7 12:28 __init__.py

In a previously empty directory, touch created a new file called __init__.py, containing zero bytes—in other words it is empty. Say instead I wanted to create a file in a directory:

$ touch subdirectory/__init__.py touch: cannot touch `subdirectory/__init__.py': No such file or directory

In this case, the “No such file or directory” is referring to “subdirectory/”. Programs like touch will only create normal files, and will not automatically create directories to contain those files. Directories, being special cases, must be created with a command-line program called `mkdir`:

$ mkdir subdirectory $ touch subdirectory/__init__.py $ ls -l total 4 drwxr-xr-x 2 embray science 4096 Sep 7 12:36 subdirectory $ ls -l subdirectory/ total 0 -rw-r--r-- 1 embray science 0 Sep 7 12:36 __init__.py

`mkdir` works similarly to `touch` and other programs that act on the filesystem, in that it may be given a relative name of a directory or a full path starting from root, so long as every directory in the path already exists. That is, one cannot create a new directory unless every directory above it already exists. Fortunately, most implementations of `mkdir` provide a shortcut for creating a path of directories, using the `—parents` option, or `-p` for short:

$ mkdir -p subdirectory/a/b/ $ ls -l subdirectory/a total 4 drwxr-xr-x 2 embray science 4096 Sep 7 12:41 b

To remove a file, use the `rm` command. Unadorned by options, `rm` can only remove simple single files—not directories:

$ rm subdirectory/__init__.py rm: remove regular empty file `subdirectory/__init__.py'? y $ ls subdirectory/ a $ rm subdirectory/ rm: cannot remove directory `subdirectory/': Is a directory

If I were to complete this section I would go on to explain `rmdir`, `rm -r`, `rm -f`, etc.

A Counterexample

Sometimes creating or deleting a file or directory will fail unexpectedly with a message like:

$ rm -f /etc/mtab rm: cannot remove `/etc/motd': Permission denied

This example leads into a discussion of file permissions.

I spent about 3 and half hours on this—one and a half were spent on the reading, but I’m a slow reader. It’s surprisingly difficult and time-consuming to think about how to explain these concepts.