Version Control With Git: Local Operations

Motivation

Dr. Ima Wolf and the Countess of Transylvania have been hired by Universal Missions (a space services spinoff from Euphoric State University) to figure out where the company should send its next planetary lander. They're both fairly nocturnal and want to be able to work on the plans at the same time, but they have run into problems doing this in the past, especially on full moons. If they take turns, each one will spend a lot of time waiting for the other to finish, but if they work on their own copies and email changes back and forth things will be lost, overwritten, duplicated, or shredded by a wolf in the night.

The right solution is to use version control to manage their work. Version control is better than mailing files back and forth because:

- Nothing that is committed to version control is ever lost. This means it can be used like the "undo" feature in an editor, and since all old versions of files are saved it's always possible to go back in time to see exactly who wrote what on a particular day, or what version of a program was used to generate a particular set of results.

- It keeps a record of who made what changes when, so that if people have questions later on, they know who to ask.

- It's hard (but not impossible) to accidentally overlook or overwrite someone's changes, because the version control system highlights them automatically.

This lesson shows how to use a popular open source version control system called Git. It is more complex than some alternatives, but it is widely used, primarily because of a hosting site called GitHub. No matter which version control system you use, the most important thing to learn is not the details of their more obscure commands, but the workflow that they encourage.

git : What is Version Control ?

Very briefly, version control is a way to keep a backup of changing files, to store a history of those changes, and most importantly to allow many people in a collaboration to make changes to the same files concurrently. There are a lot of version control systems. Wikipedia provides both a nice vocabulary list and a fairly complete table of some popular version control systems and their equivalent commands.

What problems does version control solve?

- undo mistakes by rolling back to earlier versions

- run and test with older versions for debugging (when did it break?)

- allows you to keep and switch between multiple verisons of code

- automatic merging of edits by different people

- can distribute and publish analysis, code, and workflows

- archive or back up your thesis so when your laptop goes away, your thesis doesn't

Today, we'll be using git. Git is an example of a distributed version control system, distinct from centralized version control systems. I'll make the distinction clear later, but for now, the table below will suffice.

Version Control System Tool Options

- Distributed

- Decentralized CVS (dcvs)

- mercurial (hg)

- git (git)

- bazaar (bzr)

- Centralized

- concurrent versions system (cvs)

- subversion (svn)

git clone : Getting Code

You may have seen git already if we asked everyone to run

git clone http://github.com/swcarpentry/2014-04-14-wise

This created a copy of the software carpentry repository materials on

each of your hard drives yesterday morning. If you did this already,

you don't need to to it again.

But, the instructors may have changed the content on github since that time, so now the repositories on all our hard drives are out of date.

cd

cd 2014-04-14-wise

git pull

will try to retrieve all recent changes and update your local copies. Note: git commands work only when executed from within the directory that contains the repository.

git –help : Getting Help

The first thing I like to know about any tool is how to get help. From the command line type

$ man git

The manual entry for the git version control system will appear before you. You may scroll through it using arrows, or you can search for keywords by typing / followed by the search term. I'm interested in help, so I type /help and then hit enter. It looks like the syntax for getting help with git is git –help.

To exit the manual page, type q.

Let's see what happens when we type :

$ git --help

Excellent, it gives a list of commands it is able to help with, as well as their descriptions.

$ git --help

usage: git [--version] [--exec-path[=<path>]] [--html-path]

[-p|--paginate|--no-pager] [--no-replace-objects]

[--bare] [--git-dir=<path>] [--work-tree=<path>]

[-c name=value] [--help]

<command> [<args>]

The most commonly used git commands are:

add Add file contents to the index

bisect Find by binary search the change that introduced a bug

branch List, create, or delete branches

checkout Checkout a branch or paths to the working tree

clone Clone a repository into a new directory

commit Record changes to the repository

diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

grep Print lines matching a pattern

init Create an empty git repository or reinitialize an existing one

log Show commit logs

merge Join two or more development histories together

mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

pull Fetch from and merge with another repository or a local branch

push Update remote refs along with associated objects

rebase Forward-port local commits to the updated upstream head

reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

show Show various types of objects

status Show the working tree status

tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

See 'git help <command>' for more information on a specific command.

git config : Controlling the behavior of git

Since we're going to be doing science, which is fueled by intellectual attribution, we need to perform a one-time per computer configuation of git so git knows who to credit for our contributions to the version control system.

The first time we use Git on a new machine, we need to configure a few things (we'll insert blank lines between groups of shell commands to make them easier to read):

$ git config --global user.name "Countess Vania"

$ git config --global user.email "vania@tran.sylvan.ia"

$ git config --global color.ui "auto"

$ git config --global core.editor "nano"

(Please use your own name and email address instead of the Countess of Transylvania's,

and please make sure you choose an editor that's actually on your system

if you don't have nano.)

Git commands are written git verb,

where verb is what we actually want it to do.

In this case,

we're telling Git:

- our name and email address,

- to colorize output,

- what our favorite text editor is, and

- that we want to use these settings globally (i.e., for every project),

The four commands above only need to be run once. Git will remember the settings until we change them.

git init : Creating a Local Repository

To keep track of numerous versions of your work without saving numerous copies, you can make a local repository for it on your computer. What git does is to save the first version, then for each subsequent version it saves only the changes. That is, git only records the difference between the new version and the one before it. With this compact information, git is able to recreate any version on demand by adding the changes to the original in order up to the version of interest.

To create your own local (on your own machine) repository, you must initialize the repository with the infrastructure git needs in order to keep a record of things within the repository that you're concerned about. The command to do this is git init .

Exercise : Create a Local Repository

Once Git is configured, we can start using Git. Let's create a directory for our work:

$ cd ~

$ mkdir planets

$ cd planets

and tell Git to make it a repository:

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in ~/planets/.git/

If we use ls to show the directory's contents,

it appears that nothing has changed:

$ ls

But if we add the -a flag to show everything,

we can see that Git has created a hidden directory called .git:

$ ls -a

. .. .git

Git stores information about the project in this special sub-directory. If we ever delete it, we will lose the project's history.

Advanced Exercise:

Use what you've learned. You may have noticed the file called description. You can describe your repository by opening the description file and replacing the text with a description for the repository. Mine will be described as "a catalog of the planets". You may describe yours any way you like.

$ nano description

Applications sometimes create files that are not needed. For example, some applications create backup or temporary files with names like'filename.bak' and 'filename.aux' that don't really need to be watched by version control. You can ask git to ignore such files by editing the file '.git/info/exclude'. Edit the file to ignore files the end with '.bak'.

$ nano info/exclude

git ls-files --others --exclude-from=.git/info/exclude

# Lines that start with '#' are comments.

# For a project mostly in C, the following would be a good set of

# exclude patterns (uncomment them if you want to use them):

# *.[oa]

# *~

We can ask Git for the status of our project at any time like this:

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# Initial commit

#

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

We'll explain what branch master means later.

For the moment,

let's add some notes about Mars's suitability as a base.

(We'll cat the text in the file after we edit it so that you can see what we're doing,

but in real life this isn't necessary.)

$ nano mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color, blood red.

$ ls

mars.txt

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# Initial commit

#

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

#

# mars.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

git add : Staging a File

For the git repository to know which files within this directory you would like to keep track of, you must add them to version control. First, you'll need to create one, then we'll learn the git add command.

Exercise : Add a File to Your Local Repository

Step 1 : Prepare a file to add to your repository.

$ nano mars.txt &

Step 2 : Inform git that you would like to keep track of future changes in this file.

$ git add mars.txt

Step 3: Check that the right thing happened, with git status :

$ git status

# On branch master

#

# Initial commit

#

# Changes to be committed:

# (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

#

# new file: mars.txt

#

git commit : Saving a Snapshot

In order to save a snapshot of the current state (revision) of the repository, we use the commit command. This command is always associated with a message describing the changes since the last commit and indicating their purpose. Informative commit messages will serve you well someday, so make a habit of never committing changes without at least a full sentence description.

ADVICE: Commit often

In the same way that it is wise to often save a document that you are working on, so too is it wise to save numerous revisions of your code. More frequent commits increase the granularity of your undo button.

ADVICE: Write good commit messages

There are no hard and fast rules, but good commits are atomic: they are the smallest meaningful change. A good commit message usually contains a one-line description followed by a longer explanation if necessary. Remember, you will be writing commit messages for yourself as much as for anyone else.

Our repo should have some good commit messages.

Exercise : Commit Your Changes

Git now knows that it's supposed to keep track of this file, but it hasn't yet recorded any changes for posterity. To get it to do that, we need to run one more command:

$ git commit -m "Starting to think about Mars"

[master (root-commit) f22b25e] Starting to think about Mars

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 mars.txt

When we run git commit,

Git takes everything we have told it to save using git add

and stores a copy permanently inside the special .git directory.

This permanent copy is called a revision

and in this case it is identify by f22b25e (your revision will

have another identifier).

We use the -m flag (for "message")

to record a comment that will help us remember later on what we did and why.

If we just run git commit without the -m option,

Git will launch nano (or whatever other editor we configured at the start)

so that we can write a longer message.

If we run git status now, we can admire our work:

$ git status

# On branch master

nothing to commit (working directory clean)

it tells us everything is up to date.

git log : Viewing the History

If we want to know what we've done recently, we can ask Git to show us the project's history. A log of the commit messages is kept by the repository and can be reviewed with the log command.

$ git log

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Countess Vania <vania@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Starting to think about Mars

There are some useful flags for this command, such as

-p

-3

--stat

--oneline

--graph

--pretty=short/full/fuller/oneline

--since=X.minutes/hours/days/weeks/months/years or YY-MM-DD-HH:MM

--until=X.minutes/hours/days/weeks/months/years or YY-MM-DD-HH:MM

--author=<pattern>

Making Changes

Now suppose the Countess adds more information to the file:

$ nano mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color, blood red.

The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

Git knows this file is on the list of things it's managing.

If we run git status,

it tells us the file has been modified:

$ git status

# On branch master

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

#

# modified: mars.txt

#

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

git diff : Viewing the Differences

The last line is the key phrase:

"no changes added to commit".

We have changed this file,

but we haven't committed to making those changes yet.

Let's double-check our work using git diff,

which shows us the differences between

the current state of the file

and the most recently saved version:

$ git diff

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..315bf3a 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,2 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

The output is cryptic because

it is actually a series of commands for tools like editors and patch

telling them how to reconstruct one file given the other.

If we can break it down into pieces:

- The first line tells us that Git is using the Unix

diffcommand to compare the old and new versions of the file. - The second line tells exactly which revisions of the file

Git is comparing;

df0654aand315bf3aare unique computer-generated labels for those revisions. - The remaining lines show us the actual differences

and the lines on which they occur.

The numbers between the

@@markers indicate which lines we're changing; the+on the lines below show that we are adding lines.

Advanced aside

There are many diff tools that do the same thing.

If you have a favorite you can set your default git diff tool to execute that one. Git, however, comes with its own diff system.

Let's recall the behavior of the diff command on the command line. Choosing two files that are similar, the command :

$ diff file1 file2

will output the lines that differ between the two files. This information can be saved as what's known as a patch, but we won't go deeply into that just now.

The only difference between the command line diff tool and git's diff tool is that the git tool is aware of all of the revisions in your repository, allowing each revision of each file to be treated as a full file.

Thus, git diff will output the changes in your working directory that are not yet staged for a commit. To see how this works, make a change in your readme.rst file, but don't yet commit it.

$ git diff

A summarized version of this output can be output with the –stat flag :

$ git diff --stat

To see only the differences in a certain path, try:

$ git diff HEAD -- [path]

To see what IS staged for commit (that is, what will be committed if you type git commit without the -a flag), you can try :

$ git diff --cached

Restaging a file

Let's commit our change:

$ git commit -m "Concerns about Mars's moons on my furry friend"

# On branch master

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

#

# modified: mars.txt

#

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Whoops:

Git won't commit because we didn't use git add first.

Let's do that:

$ git add mars.txt

$ git commit -m "Concerns about Mars's moons on my furry friend"

[master 34961b1] Concerns about Mars's moons on my furry friend

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

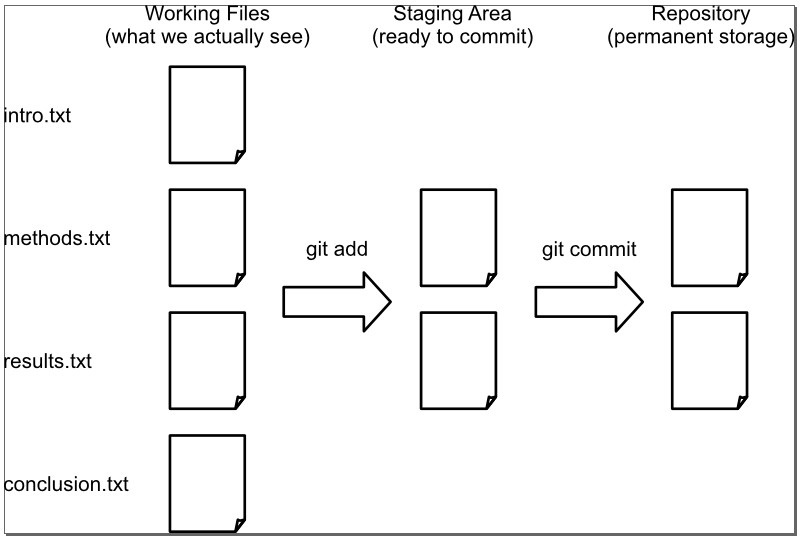

Git insists that we add files to the set we want to commit

before actually committing anything

because we often won't commit everything at once.

For example,

suppose we're adding a few citations to our supervisor's work

to our thesis.

We might want to commit those additions,

and the corresponding addition to the bibliography,

but not commit the work we've been doing on the conclusion.

To allow for this,

Git has a special staging area

where it keeps track of things that have been added to

the current change set

but not yet committed.

git add puts things in this area,

and git commit then copies them to long-term storage:

The following commands show this in action:

$ nano mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

$ git diff

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

So far, so good:

we've made a change,

and git diff tells us what it is.

Now let's put that change in the staging area

and see what git diff reports:

$ git add mars.txt

$ git diff

There is no output: as far as Git can tell, there's no difference between what it's been asked to save permanently and what's currently in the directory. However, if we do this:

$ git diff --staged

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

it shows us the difference between the last committed change and what's in the staging area. Let's save our changes:

$ git commit -m "Thoughts about the climate"

[master 005937f] Thoughts about the climate

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

check our status:

$ git status

# On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

and look at the history of what we've done so far:

$ git log

git log

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5

Author: Countess Vania <vania@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Thoughts about the climate

commit 34961b159c27df3b475cfe4415d94a6d1fcd064d

Author: Countess Vania <vania@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:07:21 2013 -0400

Concerns about Mars's moons on my furry friend

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Countess Vania <vania@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Starting to think about Mars

If we want to see what we changed when,

we use git diff again,

but refer to old versions

using the notation HEAD~1, HEAD~2, and so on:

$ git diff HEAD~1 mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

$ git diff HEAD~2 mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

HEAD means "the most recently saved version".

HEAD~1 (pronounced "head minus one")

means "the previous revision".

We can also refer to revisions using

those long strings of digits and letters

that git log displays.

These are unique IDs for the changes,

and "unique" really does mean unique:

every change to any set of files on any machine

has a unique 40-character identifier.

Our first commit was given the ID

f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b,

so let's try this:

$ git diff f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

That's the right answer, but typing random 40-character strings is annoying, so Git lets us use just the first few:

$ git diff f22b25e mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Dr. Wolf

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

All right: we can save changes to files and see what we've changed—how can we restore older versions of things? Let's suppose we accidentally overwrite our file:

$ nano mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

We will need to manufacture our own oxygen

git status now tells us that the file has been changed,

but those changes haven't been staged:

$ git status

# On branch master

# Changes not staged for commit:

# (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

# (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

#

# modified: mars.txt

#

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

git reset : Going Back

We can put things back the way they were like this:

$ git reset --hard HEAD

HEAD is now at 005937f Thoughts about the climate

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

The --hard argument to git reset tells it to throw away local changes:

without that,

git reset won't destroy our work.

HEAD tells git reset that we want to put things back to

the way they were recorded in the HEAD revision.

(Remember,

we haven't done a git commit with these changes yet,

so HEAD is still where it was.)

We can use git reset --hard HEAD~55 and so on

to back up to earlier revisions,

git reset --hard 34961b1 to back up to a particular revision,

and so on.

git checkout : Discarding unstaged modifications (git checkout has other purposes)

But what if we want to recover somes files without losing other work we've done since? For example, what if we have added some material to the conclusion of our paper that we'd like to keep, but we want to get back an earlier version of the introduction? In that case, we want to check out an older revision of the file, so we do something like this:

$ git checkout 123456 mars.txt

but use the first few digits of an actual revision number instead of 123456. To get the right answer, we must use the revision number that identifies the state of the repository before the change we're trying to undo. A common mistake is to use the revision number of the commit in which we made the change we're trying to get rid of:

The fact that files can be reverted one by one tends to change the way people organize their work. If everything is in one large document, it's hard (but not impossible) to undo changes to the introduction without also undoing changes made later to the conclusion. If the introduction and conclusion are stored in separate files, on the other hand, moving backward and forward in time becomes much easier.

git rm : Removing a file

git rm filename (Removes a file from the repository)

git mv : Moving a file

git mv filename (Renames a file in the repository)

Exercise :

1) Create 5 files in your directory with one line of content in each file.

2) Commit the files to the repository.

3) Change 2 of the 5 files and commit them.

4) Undo the changes in step 3)

5) Print out the last entry in the log.

git branch : Listing, Creating, and Deleting Branches

Branches are pointers to a version of a repository that can be edited and version controlled in parallel. They are useful for pursuing various implementations experimentally or maintaining a stable core while developing separate sections of a code base.

Without an argument, the branch command lists the branches that exist in your repository.

$ git branch

* master

The master branch is created when the repository is initialized. With an argument, the branch command creates a new branch with the given name.

$ git branch

$ git branch

* master

experimental

To delete a branch, use the -d flag.

$ git branch -d experimental

$ git branch

* master

git checkout : Switching Between Branches, Abandoning Local Changes

The git checkout command allows context switching between branches as well as abandoning local changes.

To switch between branches, try

$ git branch newbranch

$ git checkout newbranch

$ git branch

How can you tell we've switched between branches? When we used the branch command before there was an asterisk next to the master branch. That's because the asterisk indicates which branch you're currently in.

Also, there's a neat trick using bashrc which is way better. To never wonder again, put this in your ~/.bashrc file:

parse_git_branch() {

git branch 2> /dev/null | sed -e '/^[^*]/d' -e 's/* \(.*\)/(\1)/'

}

if [ "$color_prompt" = yes ]; then

PS1="${debian_chroot:+($debian_chroot)}\[\033[01;32m\]\u@\h\[\033[00m\]:\[\033[01;34m\]\w\[\033[00m\]\$(parse_git_branch) $ "

else

PS1="${debian_chroot:+($debian_chroot)}\u@\h:\w\$(parse_git_branch) $"

fi

unset color_prompt force_color_prompt

git merge : Merging Branches

At some point, the experimental branch may be ready to become part of the core or two testing branches may be ready to be combined for further integration testing. The method for combining the changes in two parallel branches is the merge command.

Exercise : Create and Merge Branches

Step 1 : Create two new branches and list them

$ git branch first

$ git branch second

Step 2 : Make changes in each new branch and commit them.

$ git checkout first

Switched to branch 'first'

$ touch firstnewfile

$ git add firstnewfile

$ git commit -am "Added firstnewfile to the first branch."

[first 68eba44] Added firstnewfile to first branch.

0 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 firstnewfile

$ git checkout second

Switched to branch 'second'

$ touch secondnewfile

$ git add secondnewfile

$ git commit -am "Added secondnewfile to the second branch."

[second 45dd34c] Added secondnewfile to the second branch.

0 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 secondnewfile

Step 3 : Merge the two branches into the core

$ git checkout first

Switched to branch 'first'

$ git merge second

Merge made by recursive.

0 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 secondnewfile

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge first

Updating 1863aef..ce7e4b5

Fast-forward

0 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 firstnewfile

create mode 100644 secondnewfile

git clone : Copying a Repository

Yesterday, you checked out a git type repository at https://github.com/swcarpentry/2014-04-14-wise

When you clone the Original repository, the one that is created on your local machine is a copy, and contains both the contents and the history. With the right configuration, you can share your changes with your collaborators and import changes that others made in their versions. You can also update the original repository with your changes.

We'll get to that soon, but for now, let's move on to a fairly easy-to-use system for managing repositories.

Exercise : Cloning Another Repository from GitHub

Step 1 : Pick any repository you like. There are many cool projects hosted on github. Take a few minutes here, and pick a piece of code.

Step 2 : Clone it. If you didn't find anything cool, you can chose the "instructional" Spoon-Knife repository:

$ cd

$ git clone git@github.com/octocat/Spoon-Knife.git

Cloning into Spoon-Knife...

remote: Counting objects: 24, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (21/21), done.

remote: Total 24 (delta 7), reused 17 (delta 1)

Receiving objects: 100% (24/24), 74.36 KiB, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (7/7), done.

Step 3 : You should see many files download themselves onto your machine. Let's make sure it worked. Change directories to the source code and list the contents.

$ cd Spoon-Knife

$ ls

git pull : Pulling updates from the Original Repository

Updating your repository is like voting. You should update early and often especially if you intend to contribute back to the upstream repository and particularly before you make or commit any changes. This will ensure you're working with the most up-to-date version of the repository. Updating won't overwrite any changes you've made locally without asking, so don't get nervous. When in doubt, update.

$ git pull

Already up-to-date.

Since we just pulled the repository down, we will be up to date unless there has been a commit by someone else to the Original repository in the meantime.